A flaw in the welfare system is preventing young people in supported housing from achieving their potential.

Supported housing is designed to help young people build the skills and confidence needed to live independently, with a key focus on improving their employment prospects. By offering stability and tailored support, it provides a crucial stepping stone toward long-term work and financial independence.

Yet the way benefits are configured for people in supported housing creates a clear disincentive for them to take up work or progress in employment. Instead of helping young people move forward, the system holds them back at the very point when they are ready to build their futures.

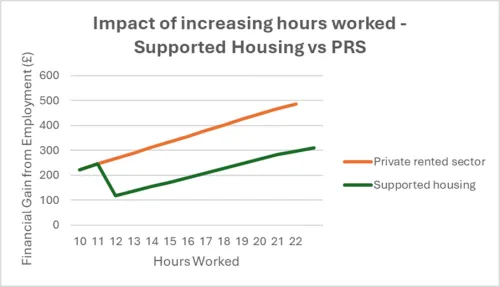

For those in private renting, increasing their earnings leads to a gradual tapering of support, allowing them to see steady improvements in their financial situation. But for young people in supported housing, the system is much harsher. Because their benefits are split between Universal Credit (UC) and Housing Benefit (HB), they face a steeper and more punitive withdrawal of support as soon as they enter or progress in work. This structural difference leaves them worse off than their peers and creates a significant barrier to building independence.

The way Housing Benefit and Universal Credit interact creates a financial “cliff edge” for young people in supported housing. With Housing Benefit tapering at 65%, an increase in working hours can see benefits withdrawn faster than earnings rise leaving some young people worse off overall. This makes rent unaffordable, increases the risk of arrears, and undermines housing stability.

The impact is stark. Many young people hesitate to enter work for fear of losing vital support, while others turn down job offers because the hours would make their rent unsustainable. Faced with such uncertainty, the current system creates anxiety and forces young people to choose between financial security and progressing in work.

The solution?

To address this, the Government can implement two targeted changes to the benefits system that would remove this disincentive, support young people into sustainable employment, and enable smooth transitions from supported housing into independent living.

1. We recommend that the Housing Benefit disregard is increased from £5 to £57.

The Housing Benefit disregard is the amount of a person’s earnings or income that is excluded from benefit calculations, so increasing this would ensure that most young people living in supported accommodation would not face a financial cliff edge and instead would be incrementally better off as they increase their working hours. Increasing disregard rates supports employment goals, reduces benefit traps, and promotes long-term independence; it could be the difference between a stable step forward to independence or a return to crisis.

2. Reduce the taper rate from 65% to 55% to bring it in line with Universal Credit.

In addition to raising the disregard, parity between the Universal Credit and Housing Benefit taper rates is required to remove the work disincentive. We recommend the government reduces the Housing Benefit taper rate from 65% to 55% to bring it in line with Universal Credit. This would effectively reduce the amount that young people living in supported accommodation are being taxed for accessing work, as their Housing Benefit would be reduced at a lower rate than it currently is (55p for every pound earned, as opposed to 65p on every pound).

To eliminate the cliff edge for all, both measures are needed. Taken together, these two measures will remove barriers to employment that are currently experienced by young people in supported housing. This will create a clear progression whereby as young people increase their hours and progress in work, they see their incomes increase and can build financial resilience to move on into independent accommodation.

Our new cost benefit analysis (see briefing below for tables and methodology) finds that if the government were to increase the disregard to £57 and reduce the taper rate to 55%:

- The government would have a net benefit of almost £13 million, in just one year, when accounting for unmonetised benefits.

- The Treasury would save almost £5 million, in just one year, when looking solely at the fiscal impacts of the policy.

The net benefit is large and driven by the savings of incentivising young people into employment. This analysis only looks at the impact over one year, and so in the long run impacts on Treasury costs ae likely to be even more beneficial, given the long-term benefits of employment on employees, and the likelihood of someone remaining in employment once they have started a job.

The analysis demonstrates that the two proposed asks of increasing the disregard to £57 and reducing the housing benefit taper rate to 55% in line with universal credit, would not only support young people into entering employment and obtaining housing security, but be financially beneficial for the government.

Our full briefing and methodological notes provide further details.