Linda Hill started working at the night shelter in Soho in May 1979, becoming Team Leader the next year and staying until January 1986. Working in the shelter was, to put it lightly, “a pattern that was very disruptive to one’s sleep."

At the time they took in 30 young people a night, many of whom had just arrived in London. But of course, they occasionally took in more: “The most we ever had was 42 – it was a bit of a nightmare, there were mattresses all over the floor. Health and safety would have had a fit!”

The want to put a roof over as many heads as possible came as homelessness soared in London through the 80s during Margaret Thatcher’s administration. This was in part due to house price inflation; mounting unemployment; a rise in drug, alcohol and mental health problems; and a ban on 16- and 17-year-olds claiming housing benefits.

London is many things to many people, and has always been a beacon city for the UK’s LGBTQ+ youth. Research has found an alarming amount of people find themselves forced out of their family or community upon revealing their sexual orientation, and this is one of the main reasons LBGT youth tend to leave home. That feeling of not fitting in draws them to places like London where there is thought to be a sense of belonging, thanks to its long-established LGBTQ+ communities.

Two people standing outside St. Anne's Soho

But without pre-established connections, many LGBT youth find themselves sleeping rough. Luckily Centrepoint was, and remains, a place for young people to take shelter. After staying the night, staff would spend the next day helping them create a plan of action that would help to move them on from homelessness.

In 1982, Terrence Higgins became one of the first people to die of an AIDS-related illness in the UK. In America, cases were picking up speed. As the 80s unfurled, HIV thrived, and by 1987 there were cases on every continent. At the start of the decade, though, there were only concerned murmurs. “In the early 80s, there was an awareness,” says Linda. “But at that time we were more concerned about Hepatitis C. All of us were nervous about possibly picking up infections. There was a risk with young men selling sex, or intravenous drug users – although they were rare – but there was a sense of, ‘let’s be realistic here’. We would be very careful if someone had an open wound or was bleeding.”

As AIDS gained prominence through the 80s, staff at the night shelter became more cautious. The fear was setting in. “I remember saying to people, ‘we need to keep everything very clean’,” Linda remembers. David Orr spent four months working in the night shelter before being promoted to Social Work Co-ordinator for six years, which saw him working across the night shelters, Centrepoint House and other new projects. “It felt like a bit of denial, but there was a growing level of awareness,” he says. “There was concern and people were scared.”

We are now well aware that HIV can affect anyone, but back then, with so little information available, many believed it was a virus that only affected gay men. Despite the anxiety this was now causing, it wasn’t something staff openly discussed in the shelter. “We did have gay staff and volunteers,” says Linda. “But it wasn’t something people were open about – although there was plenty of liberation in London, there was still stigma attached.”

The 80s progressed, and improvements were made to the shelter to create a more welcoming place. There was what David called a “youth club atmosphere”: booths like you’d find in a pub allowed people to chat freely and the food provided was comforting and familiar, creating a level of connection for those who’d often feel severely disconnected to the world around them.

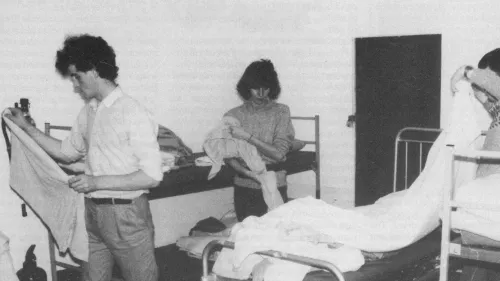

1980s Centrepoint night shelter

Despite the transient nature of the night shelter, there was still a real community spirit: “Punks worked there, an elderly nun, city workers – such a huge variety, which was amazing,” Linda remembers fondly. David has similar warm memories: “Once we’d made some changes to the night shelter and people could come back more often, it was more forgiving. Some young people would get to know staff and volunteers.”

Outside the shelter, however, London remained a ruthless place. Whilst political and social movements from the 70s had led to increased visibility for gay men and women, this was now Thatcher’s England. The Prime Minister ran a socially repressive and specifically anti-homosexual regime: Section 28 was a Thatcherite law passed in '88 that prohibited schools and councils from "promoting the teaching of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship."

As Peter Tatchell, human rights and LGBTQ+ activist, puts it, “It was open season on queers.” The epidemic was used to demonise the LGBT community. But the community fought back: queer Londoners organised themselves within the context of the political climate, and while more and more gay men were being convicted for consensual same-sex behaviour, 1988 had the biggest turnout for London Gay Pride it had ever seen.

As such, young gay men were particularly distrusting of police and those in positions of authority. “One of our volunteers was waiting for a friend to give him a lift after a night shift, and the police picked him up,” Linda recalls. “It wasn’t hard to see he was a young gay man. They picked him up and he went to court. It wasn’t just the young homeless people it happened to.”

Outside Victoria railway station

This wariness and distrust of authority put young gay men at risk. Historically, LGBTQ+ youths are more likely to experience sexual exploitation and substance misuse, which at that time made them more susceptible to being exposed to HIV. They are also more likely to experience targeted physical violence from others. Linda remembers the additional fear around the Dennis Nilsen murders in the early 80s: “He was offering to take [vulnerable young men] back to his place. I remember watching the news, and the first person they found was someone who used the night shelter a lot.” Malcom Barlow was 24 years old when he died – Nilsen would wait for men like him at The Golden Lion pub, opposite the doors of Centrepoint’s Dean Street shelter.

Still, London was considered the place to be for LGBTQ+ youths who didn’t feel at home in their own hometowns. Heaven first opened in 1979 and became the biggest nightclub for the queer community in Europe; that same year the artist and activist Derek Jarman moved to central London and put Soho on the map. (Jarman was diagnosed with HIV in '86 and created the artwork Ataxia - AIDS is Fun a year before he succumbed to the condition in '94.) Those who didn’t fit in found their ‘people’ - “there was just more acceptance,” as Linda says.

By the time Linda and David were coming to the end of their employment with Centrepoint in 1986, AIDS had the world tightly in its grasp. David distinctly remembers two young men who worked at Centrepoint who died far too young at the hands of the epidemic. “It was very present for those who worked at Centrepoint,” he remembers. “I knew them both. One died after I left, and I didn’t hear about it for a while. I think the other man left London before he died.” As Tracey Ann Oberman’s character says in It’s a Sin, “There are a lot of boys going home these days… more and more, every month.”

Thanks to the hard work of many, HIV is no longer a death sentence, and can be lived with comfortably with treatment. Work is also being done to provide a more nuanced service to homeless young people in the LGBTQ+ community (although there is still a long way to go).

With better understanding comes a swifter diagnosis: HIV can now be tested for at home, and our health team easily help signpost homeless young people to a GP or sexual health services for a test if they have any worries. But the sacrifice for such learnings was the lives of millions of men, and women, the world over. This LGBT History Month, we remember them: those who came through our doors, those who fought hard, those who dared to be true to themselves, during this perilous and heart-breaking moment in history.

For more information on being tested for HIV at home, click here.